Introduction#

Reverse engineering C++ binaries can seem daunting when you first encounter classes and object-oriented programming constructs in assembly. In this post, we’ll demystify how C++ classes work at the assembly level by exploring Lab20-01 from Practical Malware Analysis. We’ll cover the fundamentals of class instantiation, the __thiscall calling convention, and how high-level abstractions like encapsulation disappear during compilation. By the end, you’ll see how straightforward it is to identify and reverse engineer C++ classes, and we’ll recreate the original source code of a simple malware sample that downloads files using the Windows API.

The Abstraction of Classes#

Well, if you missed the Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) class, I don’t blame you. When I first started to learn about that, I felt so bored. I thought, “Why do I need to use OOP if I already have functions and structs?” I didn’t see the usability (at least in my daily tasks at that time). I just got into it when I needed to abstract some patterns and then see the real power of OOP.

Unlike structures, which primarily define a new data type, classes allow you to encapsulate both data and related functions, effectively creating a new object type. But what exactly does “encapsulation” mean? Let’s quote from Wikipedia:

An object encapsulates fields and methods. A field (a.k.a. attribute or property) contains information (a.k.a. state) as a variable. A method (a.k.a. function or action) defines behavior via logic code. Encapsulation is about keeping related code together. - Wikipedia

So basically, we can create a class to represent an object from the real world, for example, a dog. A class dog will have attributes such as: name, breed, size, and age. While the methods could be: run, bark, eat, and sleep. These are just a simple example of how classes can be used.

Understanding the basics#

Before jumping into our lab, let’s just take a very basic example. We will work with 32 bit.

#include <iostream>

class MyCalc // 8 bytes

{

public:

int x = 0; // 4 bytes

int y = 0; // 4 bytes

void add()

{

std::cout << "Add Result: " << x + y << '\n';

}

void sub()

{

std::cout << "Sub Result: " << x - y << '\n';

}

};

int main(void)

{

MyCalc* obj = new MyCalc; // Instantiating an object that has dynamic storage duration.

obj->x = 4;

obj->y = 2;

obj->add();

obj->sub();

delete obj; // Deleting the object.

return 0;

}

In our main function, we start by instantiating a new object with our custom class MyCalc. We use the new operator to allocate our object in the heap.

MyCalc* obj = new MyCalc;

After we instantiate our object, we set our attributes with some values.

obj->x = 4;

obj->y = 2;

Then, we call our two methods, add and sub, to perform some operation on our previous attributes.

obj->add();

obj->sub();

And at the end, we clean the heap by calling the delete operator.

delete obj;

The __thiscall calling convention#

Before we look at our compiled example, we first need to understand one more concept, the __thiscall calling convention. So, let me quote from Microsoft documentation:

The Microsoft-specific

__thiscallcalling convention is used on C++ class member functions on the x86 architecture. It’s the default calling convention used by member functions that don’t use variable arguments (varargfunctions).Under

__thiscall, the callee cleans the stack, which is impossible forvarargfunctions. Arguments are pushed on the stack from right to left. Thethispointer is passed via registerECX, and not on the stack. - Microsoft

It’s all an illusion#

So, now that we have some basic understanding. Let’s look at the assembly level and spot those operations that are abstracted by the compiler. I will skip some “junk code” that is not necessary for our understanding, so we can focus on what matters.

Just for the sake of education, I turned off the compiler optimization to help us during analysis. But keep in mind that in a real scenario, you will probably be dealing with code optimizations from the compiler, which will abstract even more.

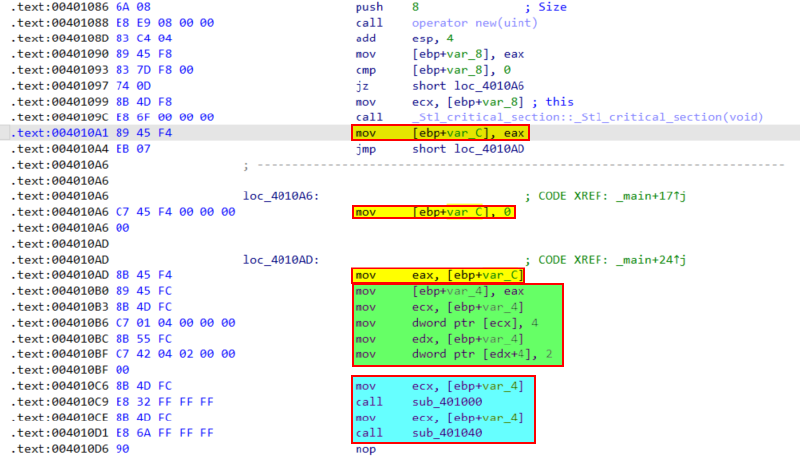

Right after the main function prologue, the block allocates 8 bytes of memory for our object and stores the returned pointer in var_C.

00401086 6A 08 push 8 ; Size

00401088 E8 E9 08 00 00 call operator new(uint)

0040108D 83 C4 04 add esp, 4

004010A1 89 45 F4 mov [ebp+var_C], eax

We can reasonably assume that those 8 bytes represent the size of our class, since we have only two 32-bit integer attributes. We can confirm this by highlighting var_C and tracing its use in the code.

The green block loads the value stored in the local var_C into EAX. Then EAX is copied to var_4. Later it’s moved into ECX, which is used as the this pointer. And in the light blue block, we call our two methods add and sub. We can create a structure in IDA to represent our class and its attributes.

typedef struct class_MyCalc // 8 bytes

{

int x;

int y;

};

After applying the correct data type, we will have something similar to this.

004010AD 8B 45 F4 mov eax, [ebp+var_C]

004010B0 89 45 FC mov [ebp+this], eax

004010B3 8B 4D FC mov ecx, [ebp+this]

004010B6 C7 01 04 00 00 00 mov [ecx+class_MyCalc.x], 4

004010BC 8B 55 FC mov edx, [ebp+this]

004010BF C7 42 04 02 00 00 mov [edx+class_MyCalc.y], 2

004010C6 8B 4D FC mov ecx, [ebp+this]

004010C9 E8 32 FF FF FF call m_add

004010CE 8B 4D FC mov ecx, [ebp+this]

004010D1 E8 6A FF FF FF call m_sub

As you can see, it becomes straightforward to spot those abstractions in assembly.

Perfect! Now we can move to what matters. You will see how easy it is to solve this lab, and how we can recreate a similar source code.

Lab20-01 Questions#

This lab is simple, but as you can see, we can learn a lot from it. Below is the question from the book.

- Does the function at

0x401040take any parameters? - Which URL is used in the call to

URLDownloadToFile? - What does this program do?

This lab is simple, but as you can see, we can learn a lot from it. Below is the question from the book.

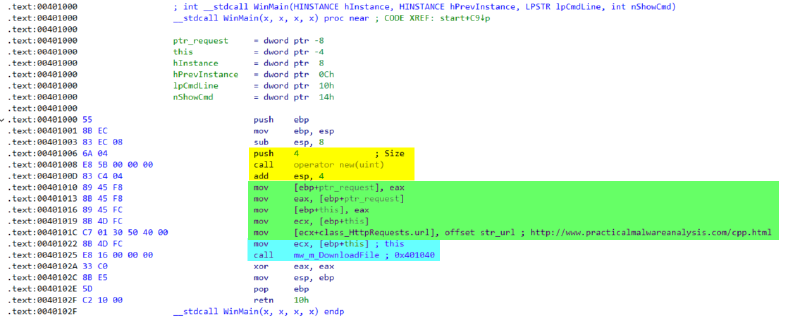

To answer the first and second questions, we need to identify the object’s creation and the this pointer. As we know from Microsoft documentation, the this pointer is passed in ECX, and if the method has any varargs, they are pushed onto the stack.

In the yellow block, the new operator allocates 4 bytes of memory for an object. In the green block, we can see that the URL is assigned to an attribute. I create a simple struct named HttpRequest in IDA to represent this class. And inside this struct, I make an attribute of char* named url. The light blue block is the call to the method that I renamed to mw_m_DownloadFile. Now, to answer question three, let’s take a look inside the method.

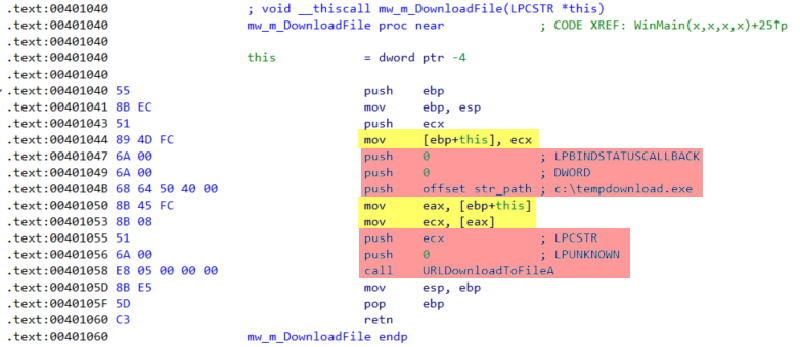

This method is pretty straightforward. It just calls the urlmon::URLDownloadToFileA passing the attribute url as the parameter. So to answer the question three, in simple terms, this binary downloads a second-stage payload and saves it in the C:\ system directory.

The reversed code#

Below, I reimplement the source code from the binary of Lab20-01.exe based on reverse engineering efforts. You can also find the Visual Studio solution on my GitHub.

#include <Windows.h>

#include <urlmon.h>

#pragma comment(lib, "Urlmon.lib")

class HttpRequest

{

public:

const char* url;

void DownloadFile()

{

::URLDownloadToFileA(

nullptr,

url,

"C:\\Users\\Public\\tempdownload.exe", // <-- New Windows versions doesn't allow an unprivileged user to write to the C:\ directory. So I use the PUBLIC just as an example.

0,

nullptr

);

}

};

int WINAPI wWinMain(

_In_ HINSTANCE hInstance,

_In_opt_ HINSTANCE hPrevInstance,

_In_ PWSTR pCmdLine,

_In_ int nCmdShow

)

{

HttpRequest* request = new HttpRequest;

request->url = "http://127.0.0.1:8000/cpp.html"; // <-- Open a CMD and run: "python3 -m http.server -b 127.0.0.1"

request->DownloadFile();

// delete request; // <-- Best practice. But, in the original binary, it doesn't use the delete operator.

return 0;

}

Conclusion#

In this blog, we learned about some C++ class concepts and how these high-level concepts disappear after compilation. We also analyze and reverse engineer Lab20-01.exe. Now we know how to identify class instantiation and, in the end, create a similar code from the lab. I hope that you liked it.